Plot Summary:

The Division of the Kingdom

The aging King Lear of Britain, wishing to divest himself of the duties of rule, decides to divide his kingdom among his three daughters: Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia. To determine the size of their shares, he demands they publicly declare their love for him. Goneril, the eldest and wife to the Duke of Albany, and Regan, the middle daughter and wife to the Duke of Cornwall, offer extravagant, flattering speeches. Pleased, Lear grants each of them a third of his kingdom.

When it is Cordelia’s turn, his youngest and most beloved daughter, she refuses to engage in flattery. She simply states that she loves him “according to my bond; no more nor less,” explaining that she must reserve half of her love for her future husband. Enraged by her honesty and perceived lack of affection, Lear disowns Cordelia completely. He strips her of her dowry and divides her portion of the kingdom between Goneril and Regan.

The Earl of Kent, a loyal nobleman, protests Lear’s rash and unjust decision. For his insolence, Lear banishes him from the kingdom on pain of death. Lear then summons Cordelia’s two suitors, the Duke of Burgundy and the King of France. Burgundy, seeing Cordelia is now dowerless, withdraws his offer of marriage. The King of France, however, is moved by her virtue and integrity, declaring she is herself a dowry, and marries her. Cordelia bids a sad farewell to her sisters, warning them about their insincere natures, before departing for France. Lear announces he will live alternately with Goneril and Regan, retaining a retinue of one hundred knights and the title of king.

The Unraveling of Family and State

Almost immediately, the consequences of Lear’s decision unfold. In a parallel plot, the Earl of Gloucester’s illegitimate son, Edmund, schemes to usurp the inheritance of his legitimate elder brother, Edgar. Edmund forges a letter that appears to show Edgar plotting to kill their father. The gullible Gloucester is easily deceived and, enraged, orders Edgar’s arrest. Edmund warns Edgar of their father’s fury, convincing him to flee and go into hiding.

Meanwhile, Lear and his knights are staying with Goneril. She quickly grows tired of their riotous behavior and sees her father’s continued authority as a threat. She instructs her steward, Oswald, and other servants to treat Lear and his knights with disrespect. Lear is infuriated by this treatment, culminating in a confrontation where Goneril demands he reduce his retinue by half. Feeling betrayed and deeply wounded by her ingratitude, Lear curses her and resolves to leave for Regan’s castle, believing his other daughter will treat him with the respect he is due. He sends the disguised Kent ahead with a letter to inform Regan of his arrival.

The Descent into the Storm

Kent arrives at Gloucester’s castle, where he finds Regan and her husband, Cornwall, have also just arrived, having left their own home to avoid receiving Lear. Kent encounters Oswald, Goneril’s steward, and picks a fight with him. The commotion draws out Regan and Cornwall, who, already biased by Goneril’s letters, take Oswald’s side and punish Kent by placing him in the stocks—an immense insult to both Kent and the king he represents.

When Lear arrives, he is outraged to find his messenger stocked. His anger grows when Regan and Cornwall refuse to speak with him. Regan, when she finally appears, proves to be as cold and unyielding as her sister. She tells Lear to return to Goneril and apologize. The situation escalates when Goneril herself arrives. The two sisters unite against their father, questioning his need for any knights at all. Regan offers to house him with twenty-five, and Goneril cruelly suggests he needs only five, or even one. Stripped of all dignity and power, Lear feels his sanity cracking. He rejects their cruel conditions and, in a fit of rage and grief, rushes out into the wilderness as a violent storm begins to rage. Regan and Cornwall order the gates of Gloucester’s castle to be locked, abandoning the old king to the tempest.

Madness on the Heath

Out on the open heath, Lear battles the storm, his internal turmoil mirroring the chaos of the elements. He is accompanied only by his loyal Fool. Kent finds them and persuades Lear to take shelter in a small hovel. There, they discover Edgar, who has disguised himself as “Poor Tom,” a mad beggar, to escape his father’s wrath. Seeing Poor Tom’s wretched state, Lear begins to empathize with the poor and destitute, realizing he has neglected them during his reign. His mind finally breaks, and he sees in the nearly naked beggar a reflection of “unaccommodated man,” the bare, essential human.

Gloucester, defying Cornwall’s orders, secretly seeks out Lear to offer him aid. He leads the king and his companions to a farmhouse for shelter. Inside, Lear’s madness intensifies, and he stages a mock trial of his absent daughters, with Edgar and the Fool as judges. Gloucester returns with news of a plot against Lear’s life and arranges for him to be carried to Dover, where Cordelia has landed with a French army.

Meanwhile, Edmund betrays his father. He shows Cornwall an incriminating letter proving Gloucester’s correspondence with the French. As a reward, Cornwall makes Edmund the new Earl of Gloucester. Cornwall and Regan then capture the old Earl and brutally interrogate him. When Gloucester defiantly admits to helping Lear, Cornwall gouges out one of his eyes. A servant, horrified by the cruelty, intervenes and mortally wounds Cornwall before being killed by Regan. Regan then helps her wounded husband gouge out Gloucester’s other eye. In a final act of cruelty, she reveals that it was Edmund who betrayed him. The blinded Gloucester, realizing Edgar’s innocence, is cast out of his own castle to wander alone.

Reunion and False Hope in Dover

The blind Gloucester is led by an old tenant. He soon encounters his son Edgar, still disguised as Poor Tom. Gloucester, overcome with despair, asks to be led to the cliffs of Dover so he can commit suicide. Edgar agrees but leads him instead to flat ground. He then vividly describes a great precipice, tricking his father into believing he has leaped from a great height and has been miraculously saved by the gods. The experience transforms Gloucester, who resolves to bear his suffering patiently.

The group then encounters Lear, now completely mad, wandering and crowned with wildflowers. He delivers a powerful, rambling speech on justice, lechery, and the hypocrisy of authority before being found by Cordelia’s attendants. He is taken to the French camp, where he is cared for and finally reunited with Cordelia. Waking from a long sleep, Lear is lucid but deeply ashamed. In a scene of profound tenderness, he kneels to his daughter, and they reconcile.

Meanwhile, political and personal tensions escalate. Goneril and Regan are now rivals for the affection of the newly powerful Edmund. Goneril sends a letter to Edmund via Oswald, urging him to kill her husband, Albany, so they can be together. Edgar intercepts the letter after killing Oswald, who was attempting to murder Gloucester for a reward.

The Final Catastrophe

The British forces, led by Albany and Edmund, confront the French army. Before the battle, Edgar, in the guise of a peasant, gives Goneril’s incriminating letter to Albany, telling him to read it after the battle and to sound a trumpet if the British are victorious, at which point a champion will appear to prove the letter’s contents.

The British army defeats the French, and Lear and Cordelia are captured. Edmund secretly gives a captain a written order to have them both killed in prison. Albany, now aware of Edmund’s treachery, arrests him for treason. He sounds the trumpet, and Edgar appears in full armor to challenge his brother. In the ensuing duel, Edgar mortally wounds Edmund.

As Edmund lies dying, the truth of his schemes is revealed. Goneril, exposed, rushes offstage. A messenger then announces that Goneril has poisoned Regan and then killed herself. The dying Edmund, moved by the tale of his father’s death (Gloucester’s heart “burst smilingly” from the extremes of grief and joy upon Edgar’s revelation), decides to do one good deed. He confesses his order to execute Lear and Cordelia and urges them to send a reprieve.

But it is too late. Lear enters, carrying the body of Cordelia, who has been hanged. In his profound grief, Lear is momentarily lucid, describing how he killed the man who was hanging her. He is surrounded by the few loyal survivors—Kent, Albany, and Edgar. Lear, holding Cordelia, believes he sees a sign of life on her lips. Then, his heart breaks, and he dies. Albany is left to rule a shattered kingdom, but Kent declares he has a journey to make, as his master is calling him. Edgar is left to speak the final, mournful lines, reflecting on the immense suffering that has transpired.

Characters:

King Lear

Lear begins the play as an absolute monarch, defined by his pride, arrogance, and a desperate need for public validation. His “love test” is not a search for genuine affection but a demand for flattery, revealing his tragic flaw: an inability to distinguish between appearance and reality. When Cordelia’s honest “Nothing” shatters his ego, his rage is swift and absolute. He banishes loyalty (Kent) and true love (Cordelia), surrendering his power to the very daughters who will destroy him. His journey is a painful stripping away of everything that defines him—his title, his retinue, his home, and finally, his sanity. Through his madness on the heath, however, Lear achieves a profound and terrible insight. He empathizes with the poor and marginalized (“O, I have ta’en too little care of this!”), recognizes the shared vulnerability of all humanity (“unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal”), and sees the corruption inherent in power and justice. His reunion with Cordelia represents a moment of profound humility and grace, but the play denies him a peaceful end, forcing him to endure the ultimate suffering of her death before his own heart breaks.

Cordelia

Cordelia embodies integrity, honesty, and unconditional love. Her refusal to participate in her father’s love test is not an act of coldness but a testament to her belief that love is a matter of deeds, not hollow words. Banished and disowned, she retains her dignity and virtue, finding a husband in the King of France who values her for who she is, not what she possesses. Her return to Britain at the head of a French army is not an act of invasion but a mission of rescue, driven by “love, dear love, and our aged father’s right.” In her reunion with Lear, she is a figure of pure forgiveness and grace, asking for his blessing and offering him comfort without a hint of reproach. Her tragic, senseless death at the end of the play is the ultimate expression of the story’s bleak vision, a moment that challenges any notion of a just and ordered universe.

Goneril and Regan

Goneril and Regan are terrifying embodiments of ambition, cruelty, and a complete lack of natural affection. They are masters of deceit, easily winning their father’s kingdom with empty flattery. Once in power, they reveal their true natures, systematically stripping Lear of his dignity and authority. Goneril is calculating and cold, the first to move against her father, while Regan is more openly sadistic, displaying a vicious pleasure in cruelty, as seen in her participation in the blinding of Gloucester. Their shared evil binds them together against their father, but their rivalry over Edmund ultimately destroys them. Their lust for power and for Edmund devolves into a venomous jealousy that leads Regan to be poisoned by Goneril, who then takes her own life. They represent a perversion of nature, a world where familial bonds are meaningless in the face of selfish desire.

Earl of Gloucester

Gloucester’s story runs parallel to Lear’s, making him a key figure in the play’s double plot. Like Lear, he is a father who makes a catastrophic error in judgment, trusting his deceitful illegitimate son, Edmund, while banishing his loyal legitimate son, Edgar. Gloucester’s blindness is initially metaphorical—he is blind to the truth of his sons’ characters. His punishment is horrifically literal: his eyes are gouged out for his loyalty to Lear. This act of extreme violence marks his turning point. Blinded, he begins to “see” the world and his own life with a new clarity, recognizing Edgar’s innocence and his own folly. His journey is one of immense suffering and despair, culminating in his attempted suicide at Dover. Saved by Edgar’s compassionate deception, he learns to endure his suffering with patience. His death, a mixture of overwhelming joy and grief upon finally recognizing Edgar, is one of the few moments of bittersweet release in the play.

Edgar

Edgar begins as a naive and trusting nobleman, easily tricked by his brother’s machinations. Forced to flee, he undergoes a profound transformation, adopting the disguise of “Poor Tom,” a mad beggar. This role is both a means of survival and a vantage point from which to observe and comment on the world’s madness. As Poor Tom, he is a symbol of humanity stripped to its barest essentials. Edgar is a fundamentally good and resilient character who acts as a guide and protector, first to the mad Lear on the heath and then to his blind father, whom he leads on a spiritual journey from despair to endurance. In the final act, he sheds his disguise to become an agent of justice, challenging and defeating Edmund in combat. As one of the few noble survivors, he is tasked with helping to restore order to the shattered kingdom, embodying hope and the endurance of virtue in a dark world.

Edmund

Edmund is the play’s primary antagonist, a charismatic and intelligent Machiavellian villain. His motivations are rooted in his social status as a bastard, which denies him the rights and respect afforded to his legitimate brother. He rejects the established social and moral order, declaring “Thou, Nature, art my goddess,” and dedicates himself to a ruthless, self-serving pursuit of power. He is a master manipulator, preying on the weaknesses of others—his father’s gullibility, his brother’s trust, and Goneril and Regan’s lust. His rise is swift and brutal, achieved through deception and betrayal. Though he expresses a brief moment of reflection before dying (“The wheel is come full circle; I am here”), and attempts a final act of good by trying to save Lear and Cordelia, his repentance comes too late to avert the final tragedy.

Earl of Kent

Kent represents the ideal of unwavering loyalty. His devotion to Lear is absolute, and he is willing to speak truth to power, even when it means his own banishment. He immediately risks his life by returning in disguise as a common servant, “Caius,” so he can continue to serve the king who cast him out. Throughout Lear’s decline, Kent is a constant source of protection and practical sense, trying to shield the king from both the storm and his own madness. He remains loyal to the very end, and his final lines—”My master calls me. I must not say no”—suggest he will soon follow Lear in death, unable to live in a world without his king.

Core Themes:

Justice and Injustice

The play relentlessly questions the existence of justice, both human and divine. Lear’s initial act of banishing Cordelia and Kent is a profound injustice that sets the tragedy in motion. The virtuous characters suffer disproportionately: Cordelia is hanged, Gloucester is blinded, and Lear is driven mad. Characters repeatedly appeal to the gods for justice (“As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods; / They kill us for their sport,” says Gloucester), but the universe often seems indifferent or cruel. While the villains ultimately receive their comeuppance—Goneril, Regan, Cornwall, and Edmund all die for their crimes—these acts of retribution feel hollow in the face of Cordelia’s senseless death. The play leaves the audience to grapple with a world where suffering is not always redemptive and where justice, if it exists at all, is brutal and often too late.

Madness and Wisdom

King Lear explores the paradoxical relationship between madness and insight. Lear’s descent into insanity is not merely a loss of reason but a journey toward a deeper, more authentic understanding of himself and the world. It is only when he is stripped of his sanity and status that he can see the emptiness of his former life, the hypocrisy of society, and the true meaning of human vulnerability. His mad conversations with Gloucester and Edgar on the heath contain some of the most profound truths in the play. Similarly, Edgar’s feigned madness as Poor Tom allows him to speak uncomfortable truths and navigate a world that has itself gone mad. The play suggests that conventional sanity can be a form of blindness, and that a breakdown of the rational mind is sometimes necessary to perceive a more essential reality.

Authority versus Chaos

The play dramatizes the breakdown of order that occurs when authority is abdicated irresponsibly. Lear’s division of the kingdom is a violation of the natural and political hierarchy, unleashing chaos that spreads from the family to the state and into the natural world itself. The family unit disintegrates into brutal conflict, the political landscape is fractured by civil strife and foreign invasion, and nature erupts in a violent storm that mirrors the “tempest” in Lear’s mind. The play portrays a world teetering on the edge of chaos, where the bonds of loyalty, family, and social order have been severed. The final scene, with the stage littered with bodies and the future of the kingdom uncertain, powerfully illustrates the devastating consequences of this collapse.

The Nature of “Nature”

The concept of “nature” is central and complex. The play contrasts two opposing views of nature. The first is a benevolent, ordered, and moral force, the basis of familial bonds and social duty. Goneril and Regan are condemned as “unnatural hags” for violating this order. The second view, championed by Edmund, is a brutal, chaotic, and amoral force where only the strong and cunning survive. Edmund worships this “Nature” as his goddess, using it to justify his selfish ambition. The play also explores the concept of essential human nature through the figure of “unaccommodated man”—man stripped of all social constructs and possessions. Lear’s encounter with the near-naked Poor Tom forces him to confront this bare, vulnerable state, questioning what it truly means to be human beyond the “lendings” of civilization.

Plot devices:

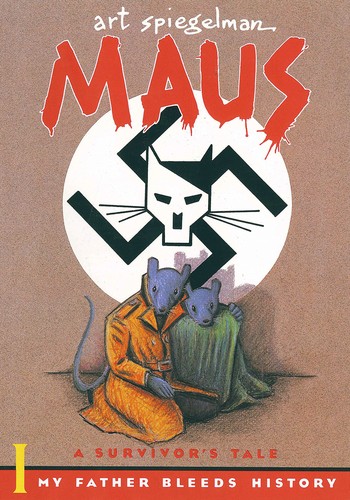

The Double Plot (Parallelism)

Shakespeare masterfully weaves together two parallel stories: the main plot of King Lear and his three daughters, and the subplot of the Earl of Gloucester and his two sons. This structural device amplifies the play’s themes, making them feel universal rather than specific to one family.

* Both fathers misjudge their children: Lear banishes his loyal daughter, Cordelia, and favors his treacherous daughters, Goneril and Regan. Gloucester banishes his loyal son, Edgar, and trusts his treacherous son, Edmund.

* Both fathers suffer betrayal and exile: Both Lear and Gloucester are cast out by the children they trusted and are forced to wander as outcasts.

* Both achieve insight through suffering: Lear finds wisdom in madness, while Gloucester learns to “see” clearly only after he is blinded.

This parallelism reinforces the play’s exploration of family betrayal, suffering, and the painful acquisition of wisdom, showing these tragedies unfolding in both the royal and noble spheres.

Disguise and Deception

Disguise is a crucial device for both survival and the exploration of identity.

* Kent’s disguise as the servant “Caius” allows him to remain by Lear’s side, offering protection and loyal counsel even after being banished. It highlights his unwavering loyalty and demonstrates that true worth is independent of title or appearance.

* Edgar’s disguise as the mad beggar “Poor Tom” is his only means of escaping death. This persona forces him to inhabit the lowest rung of society, giving him a unique perspective on suffering and madness. It also allows him to guide and ultimately save his blind father.

Both disguises create dramatic irony, as the audience is aware of the characters’ true identities while other characters are not, emphasizing the theme of appearance versus reality.

Symbolism of Blindness and Sight

The play uses the contrast between literal and metaphorical sight as a central symbol.

* Lear’s blindness is metaphorical at the start. He is “blind” to the true nature of his daughters, unable to see Cordelia’s love or Goneril and Regan’s deceit. He only begins to gain true “insight” after he loses his mind and his kingdom.

* Gloucester’s journey is the reverse. He is literally blinded by Cornwall and Regan in a horrific act of violence. This physical blindness ironically leads to his spiritual insight. As he says, “I stumbled when I saw.” No longer deceived by appearances, he finally understands Edmund’s treachery and Edgar’s loyalty. The symbol powerfully suggests that true seeing is an internal, moral act, independent of physical vision.